The patient lay lifeless on the operating table. The outlook was grim. This would be the second, and final attempt at a complex emergency surgery, the success of which would mean the difference between life and death. The surgeon’s focus was palpable throughout the sterilized operating room, silent but for the steady resonance of the cardiac monitor reporting that, despite the odds, hope endured within the patient’s all too frangible heart. As is so often the case in emergency medicine, survival would depend wholly on the judgement and precision of the attending physician, and their ability to navigate a treacherous path between multiple conflicting risk factors. On this day risk factors were popping up like jellyfish across our warming oceans, all of which were made more complicated by the patient’s hollow bones and, were the anesthesia to wear off, proclivity to tear out the good doctor’s eyes and fly away.

It was the prospect of having my own eyes torn out that occupied my attention on a blistering hot September morning last year as I headed down the Grapevine to investigate a report of a “huge eagle dying on the side of the highway.” The plan was simple enough; I would go down and see what, if anything, could be done for the bird, and if possible, transport her to our local veterinary hospital for care. As a wildlife biologist, I have a fair amount of experience handling wildlife, including large birds, but I am certainly no falconer. Wildlife rescue falls well outside the purview of my typical responsibilities with the Tejon Ranch Conservancy, but after being coached-up by a former colleague and wildlife rehabilitator, I was confident I understood how to handle and contain such a large bird without injuring it. Doing so without personally being sliced to ribbons, I was less sure. This trepidation only increased as I pulled over on the side of a dusty highway to see the gilded velociraptor hissing at me expectantly, her three-inch talons tucked beneath her like so many prison shivs. The report was accurate, she was huge, and she was certainly dying as she was completely crippled from an apparent blunt-force trauma. The golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), is one of the most potent creatures to have ever taken flight from the surface on this earth, ever. Its Herculean eyesight combined with a massive 6-foot wingspan allow it to target a full-grown deer at a distance of two miles, then dive upon its prey reaching speeds over 180 mph. From there, the pointy bits take care of the rest.

Even as this large female lay crumpled like old laundry in a forgotten closet, her auric gaze cast forth the eminence of the imperial overlord that she was born to be. As our eyes met, she seemed to take authority over my very soul. I had concerns. As I quietly approached, one thing became abundantly clear: somewhere nearby a striped skunk was recounting to his skeptical compatriots the legend of when he defeated the mighty eagle in one-on-one combat. The bird reeked. Her wretched state bedeviled further by an implacable sun grinding out her remaining lifeforce by the minute. My hope was to gently wrap her in a saddle blanket and transfer her to a large animal crate for transport, which, to my great relief, is exactly what happened. This proud, deadly predator had no fight left.

Wilder the eagle arrives gravely injured and severely dehydrated at Mountain Aire Veterinary Hospital in Frazier Park. Photo courtesy of Mountain Aire Veterinary Hospital.

While my Crocodile-Dundee moment had come to an end, the story of this bird’s recovery, and the remarkable hash of heroes who stepped forward on this creature’s behalf, was about to begin. This may come as a surprise, but many wild eagles remain uninsured, which means all of the comprehensive emergency procedures required to bring her back from the brink would be administered pro-bono. Add to that the facilities and specialized equipment necessary to care for such a large and potentially dangerous bird, it is a testament to the greatness of our civilization that I had anywhere to take her in the first place. Our tour of Southern California wildlife rescue facilities began at the Mountain Aire Veterinary Hospital in Frazier Park, where the redoubtable Dr. Cosko abandoned her well-earned day-off to treat the shattered and depleted bird. Suffice it to say, Whiskers the cat was less than thrilled as I rudely interrupted her flea treatment only to present a veritable angel of death to her attending physician.

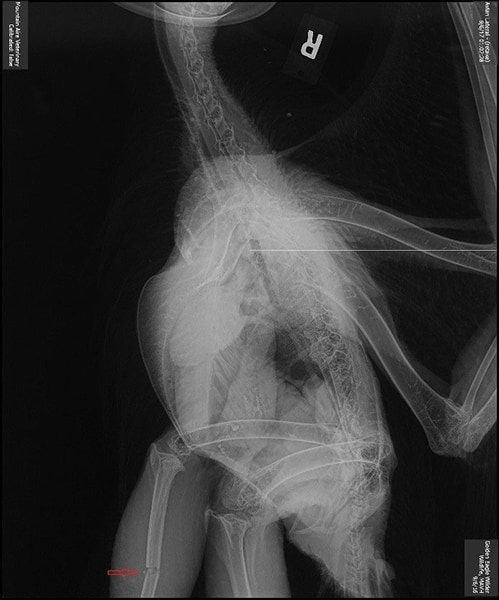

Initial exploratory x-rays performed by Mountain Aire Veterinary Hospital. X-rays reveal a comminuted fracture of the right tibia/fibula(fused). Notice the small bone fragments visible around the break site. Also notice her pneumatic bones characterized by hallow air space reinforced by lightweight honeycomb-like struts. Photo courtesy of Mountain Aire Veterinary Hospital.

As Dr. Cosko and her staff sprang into action, it was easy to see how she has become something of a local legend in our community. This is a woman who, in addition to quarterbacking the only vet hospital for 50 miles in any direction, decided to pick up a law degree in her spare time, for no other reason than to make her a more potent animal rights advocate. In the 45 minutes I spent trying, and mostly failing, to be of some assistance, I witnessed Dr. Cosko reach out and pull this bird from the jaws of death. An MRI confirmed she indeed had suffered a compound fracture of her fused tibia fibula, the large “drumstick” bone descending from the right side of her body. Fluids were administered, casts were molded, vitals were tracked, mice were proffered. But this eagle would require more.

Dr. Cosko and her team work to stabilize the injured eagle. The unusual size and shape of the eagle’s injured leg required a custom molded cast. Photo courtesy of Mountain Aire Veterinary Hospital.

Such a severe injury would require surgery to heal correctly, a prospect made more precarious by the multiple comminuted bone fragments present around the break site. This would necessitate an advanced surgical facility and rehabilitation center capable of handling a bird of her stature, not to mention a surgeon capable of performing the procedure. But where to find such a facility and how to get her there? It is not as if there is an animal ambulance service on-call for this type of situation. Enter Vicki Bingaman, a Frazier Park local and friend of the Conservancy. As a wildlife rehabber herself, we had facilitated the release of several of her animals over the years out on the Ranch, and she was known to be well-connected in wildlife rescue circles. After a brief explanation of what we were dealing with, Vicki too sprang into action, and in a matter of minutes had not only made arrangements with one of the best wildlife rehabilitation clinics in the region, but had volunteered to transport the bird as soon as she was able.

Wilder the eagle is prepared for surgery at the California Wildlife Center in Malibu.

Two days later the eagle was in surgery at the California Wildlife Center in Malibu, under the expert care of veterinary surgeon Dr. Duane Tom. Dr. Tom is another renowned figure in the world of wildlife medicine and like both Vicki and Dr. Cosko, he too is all in. Dr. Tom’s life revolves around his practice. I mean that literally as he intentionally bought a home only minutes away from his clinic, just to be available at a moment’s notice. His passion for wildlife medicine is based on the guiding philosophy that “wildlife injuries are too often caused by human interactions and it is our responsibility to do something about it.” In the case of this eagle, he certainly did. Only days after his first attempt to surgically repair the ruined bone, the eagle’s strength began to return and with that newfound vigor, managed to dislodge the pins fixing the bone in place. This was no small mishap, as the only remaining option was to refit the bone with larger, stronger fixing pins. If these larger pins failed, or if their increased diameter cracked the bone altogether, the bird would die. There was no third option, there was no back-up plan.

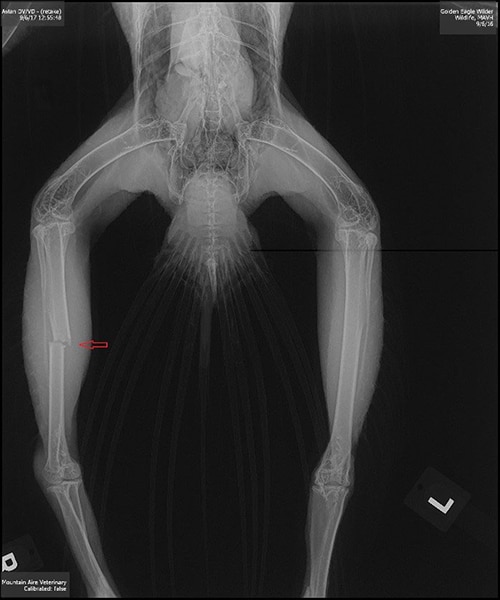

Dr. Tom uses long pins and external fixers to surgically repair the eagle’s injured leg. A similar injury to a mammalian leg would be stabilized using plates. However, since bird’s pneumatic bones do not contain marrow, plates would cut off circulation to the lower extremity as circulation occurs along the surface of the bone in birds.

A radiograph reveals long metallic pins and external fixer stabilizing the eagle’s injured leg following her initial surgery at the California Wildlife Center in Malibu. Photo courtesy of California Wildlife Center.

It is here that we began our story, and it is here, once again, that we find the steadfast determination of a few selflessly motivated individuals yank this fated bird back from the brink. Dr. Tom was successful in his second attempt at stabilizing the eagle’s leg, and after only a few short months of rehabilitation, she was ready to reign terror upon the ground squirrels of the San Joaquin Valley once again. However, successfully releasing captive eagles back into the wild is not as straightforward as it may seem, particularly when having been in captivity for an extended period. Eagles, like most raptors, are territorial predators that require an established home range to hunt, find mates, and raise young. For this reason, it was important for our eagle to be released back on Tejon close to where she was found. Not only would she be familiar with the landscape, she would have the best chance at reestablishing her former home-range and maybe even reunite with her mate. This last potentiality opens the possibility for what must be the most romantic wildlife encounter of all time: The winged paramour dolefully holds out hope, another day atop his lonely nest- useless now. Until finally, from out of the winter gloom he sees her rise again, like a golden phoenix from the valley floor, and for the first time in his eagle life he cannot believe his biologically perfect eyeballs…

Wilder the eagle, now in the final stages of recovery, waits patiently on her favorite roost at the California Wildlife Center’s open-air flight pen. Photo courtesy of California Wildlife Center.

In anticipation of our eagle’s return to Tejon, we took the opportunity to invite all the individuals who were involved in her rescue and rehabilitation to come out and observe the release. So it was, that we were all gathered together on that drizzly January afternoon, to bid farewell to what was now an almost unrecognizably resplendent eagle. She had gained a full 3 pounds while in recovery, making her a formidable 12 pounds of death from above. It occurred to me then, that such a menacing creature does not naturally invite sympathy – respect certainly, veneration even, but eagles don’t exactly call out for snuggles. Yet here she was, a soaring testament to the passionate tenacity alive within each of the selflessly motivated individuals and organizations that stepped up to save this single, intrinsically worthy lifeform. Witnessing the synchrony between these disparate groups as they came together to intercede on this animal’s behalf, there was a sense of community at work – more than that, society at work. At a time when there are so many reminders of our society’s more deleterious tendencies, this group reminds us of the power of compassionate human beings working together in service to THE OTHER, whomever that may be; in this case the we-should-all-be-thanking-our-lucky-stars-it-isn’t-twice-as-big bird we watched glide away home in the Tehachapi foothills of Tejon.

Wilder the eagle takes to the sky for the first time in almost five months, less than a quarter mile from where she was originally rescued along the southern border of Tejon Ranch. Photo courtesy of Felix Adamo/ Bakersfield Californian.

Learn more about the California Wildlife Center.